-

Book-length studies in which writing about Australia forms a significant part of the narrative are the basis of this dataset.

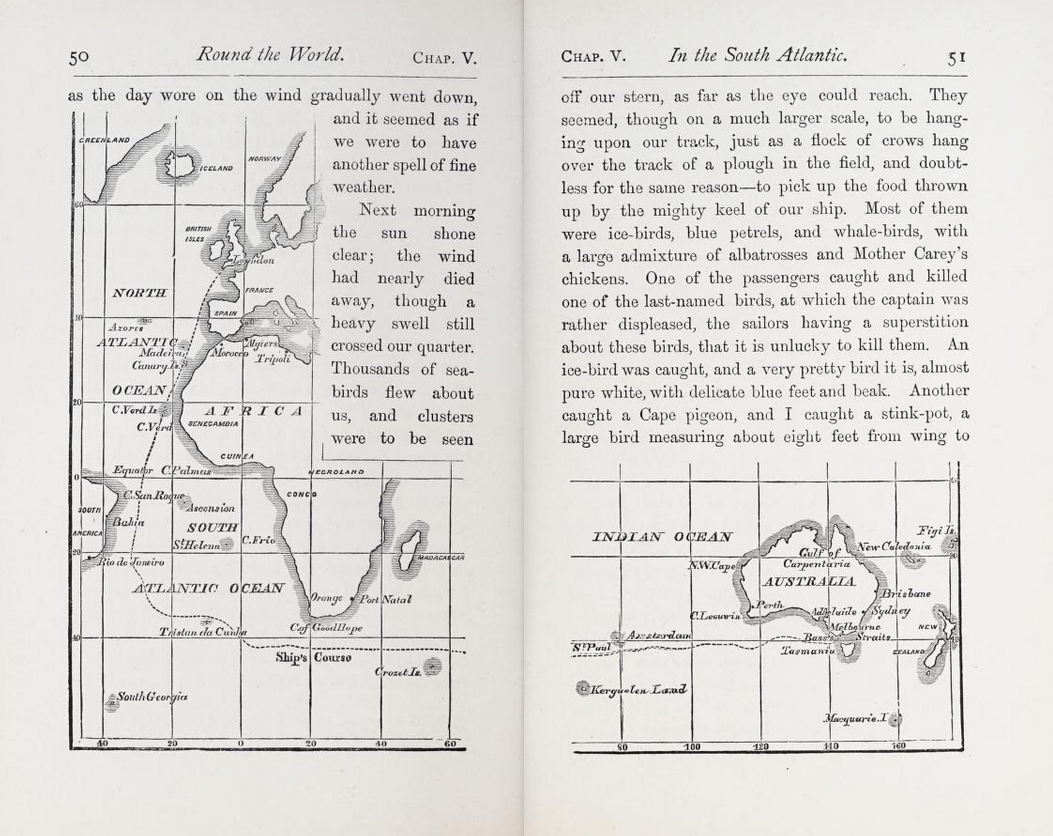

Many books include Australia as part of a world tour, which provide fascinating insights into nineteenth-century mobility and how writers compared different locations. For example, Samuel Smiles edited A Boy's Voyage Round the World (1880) based on the diary and letters of Smiles' unnamed youngest son, sent on the voyage for health reasons. Others travelled for political reasons, such as the social reformers and sisters Rosamond and Florence Hill in What We Saw in Australia (1875) and the journalist Jessie A. Ackermann, whose illustrated work The World Through a Woman’s Eyes (1896) chronicles her travels as a member of the Women's Christian Temperance Union.

Writers often serialized extracts in colonial newspapers and magazines, as links to existing AustLit records show, however this dataset focusses on book-length travel writing as a distinctive genre. Judith Johnston and Monica Anderson reveal how writing about Australia was published in the British periodical press in the same period as this dataset: see Judith Johnston and Monica Anderson, eds., Australia Imagined: Views from the British Periodical Press, 1800-1900

-

Every effort has been made to verify the author of each record, and biographical details including birth and death dates of public figures and most private travellers have been identified and cross-checked with the Australian Dictionary of Biography, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, newspaper records in Trove, and / or family history records.

Professional writers who published travel writing in addition to their fiction, journalism, and other kinds of writing are linked through AustLit’s research datasets and affiliations. These provide new insights into a figure such as Frank Fowler, for example, who has been remembered mostly as the editor of the important early Australian magazine Month: his Southern Lights and Shadows (1859) reveals his “Three Years’ Experience of Social, Literary, and Political Life in Australia”, as the subtitle describes. Other travel writers found that the Australian colonies provided evidence for major new geopolitical alliances, such as Charles Dilke in his Greater Britain: A Record of Travel in English-Speaking Countries During 1866 and 1867 (1868), C. E. R. Schwartze’s Travels in Greater Britain (1885), James Froude’s Oceana (1886), and Max O'Rell (the French journalist Paul Blouet) in John Bull & Co. The Great Colonial Branches of the Firm: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa (1894).

In 1866-1867, the 23-year-old Charles Dilke followed ‘England around the world: everywhere I was in English-speaking, or in English-governed lands’ seeking evidence for ‘a conception, however imperfect, of the grandeur of our race, already girdling the earth, which it is destined, perhaps, eventually to overspread.’ Dilke noted happily that although climate, soil, custom, and ‘mixture with other peoples had modified the blood ... in essentials the race was always one.’ Ideas of blood and race yoked together the settler colonies and Britain at the moment in which that relationship seemed vulnerable, and travel narratives which sought to fortify Anglo-Saxon grandeur bore unmistakable traces of strain even in their hyperbolic assertions of racial superiority. Coining in its title the phrase ‘Greater Britain,’ which came to represent a spectrum of late imperial politics, Dilke's best-selling travelogue embodied both the promise and the threat of a global geopolitical entity united by race and blood: 'If two small islands are by courtesy styled "Great," America, Australia, India must form a "Greater Britain"', Dilke posited. (Johnston, '"Greater Britain": Late Imperial Travel Writing and the Settler Colonies', 32).

-

Other writers might only ever have published their narrative about travelling to Australia: these amateur authors included one-off travellers and many women. Many read other travel accounts on board ship, both on the way out and the return journey, and noted their intertextual influence, either correcting their impressions, citing other writers and their statistics, or disputing earlier accounts. Many of the texts by amateur writers follow a standard narrative of shipboard life, brief trips from Australian ports into the major cities and their immediate environs, and the return journey home.

Women travel writers were mostly from middle-class to elite parts of society, from Ellen Clacy's narrative 'written on the spot' in Victoria, published as A Lady's Visit to the Gold Diggings of Australia in 1852-53, to Alice Anne Graham-Montgomery (1847-1931), Duchess of Buckingham and Chandos and Countess Egerton of Tatton, who chronicled her global tour through the publication of her letters as a book entitled Glimpses of Four Continents (1893). Women accompanied their husband or other family members from the early colonial period, such as Mary Ann Parker who wrote A Voyage Round the World, in the Gorgon Man of War (1795) after the death of her husband Captain John Parker. The artist, poet, and novelist Louisa Ann Meredith wrote a series of books beginning with Notes and Sketches of New South Wales (1844). Meredith focussed on domestic matters key to settler households in My Home in Tasmania, During a Residence of Nine Years (1852). Local colonial conditions often encouraged women such as Janet Millett to write about her Western Australian experience as a pastor’s wife in An Australian Parsonage; or, the Settler and the Savage in Western Australia (1872).

-

Religious travellers provide insight into the progress of religion and colonial morality. Some use travel only as an mechanism to discuss their conversion and spiritual journeys, such as Eliza Davies’ The Story of an Earnest Life: A Woman's Adventures in Australia (1881). Others travelled with particular religious motivations, such as the Quaker James Backhouse in A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies (1843) and Thomas Cook in Days of God's Right Hand: Our Mission Tour in Australasia and Ceylon (1896). Clergymen provided insight into their religious travels within Australia and the Asia-Pacific region, such as Henry Hussey’s The Australian Colonies; Together with Notes of a Voyage from Australia to Panama in the Golden Age (1855), John Davies Mereweather’s Diary of a Working Clergyman in Australia and Tasmania, which includes details of his return voyage home through Asia (1859), and Thomas Atkins’ The Wanderings of the Clerical Eulysses (1859), which provided insight into the controversial Norfolk Island convict settlement.

Religious travel writing provided not simply a vision of benighted heathen awaiting Christian salvation, but a complex picture - 'thick description' in Clifford Geertz's terms - of colonial cultures. Religious men, usually free from the constraints of government officials and peculiarly empowered by their marginal place in imperial regimes, bore witness in unexpected and often unsettling ways. While their travel discourses were forged in imperial crucibles of ideas about race and domination, their texts reverberate with far more challenging - even radical – ideas (Johnston, 'Writing the Southern Cross', 215).

-

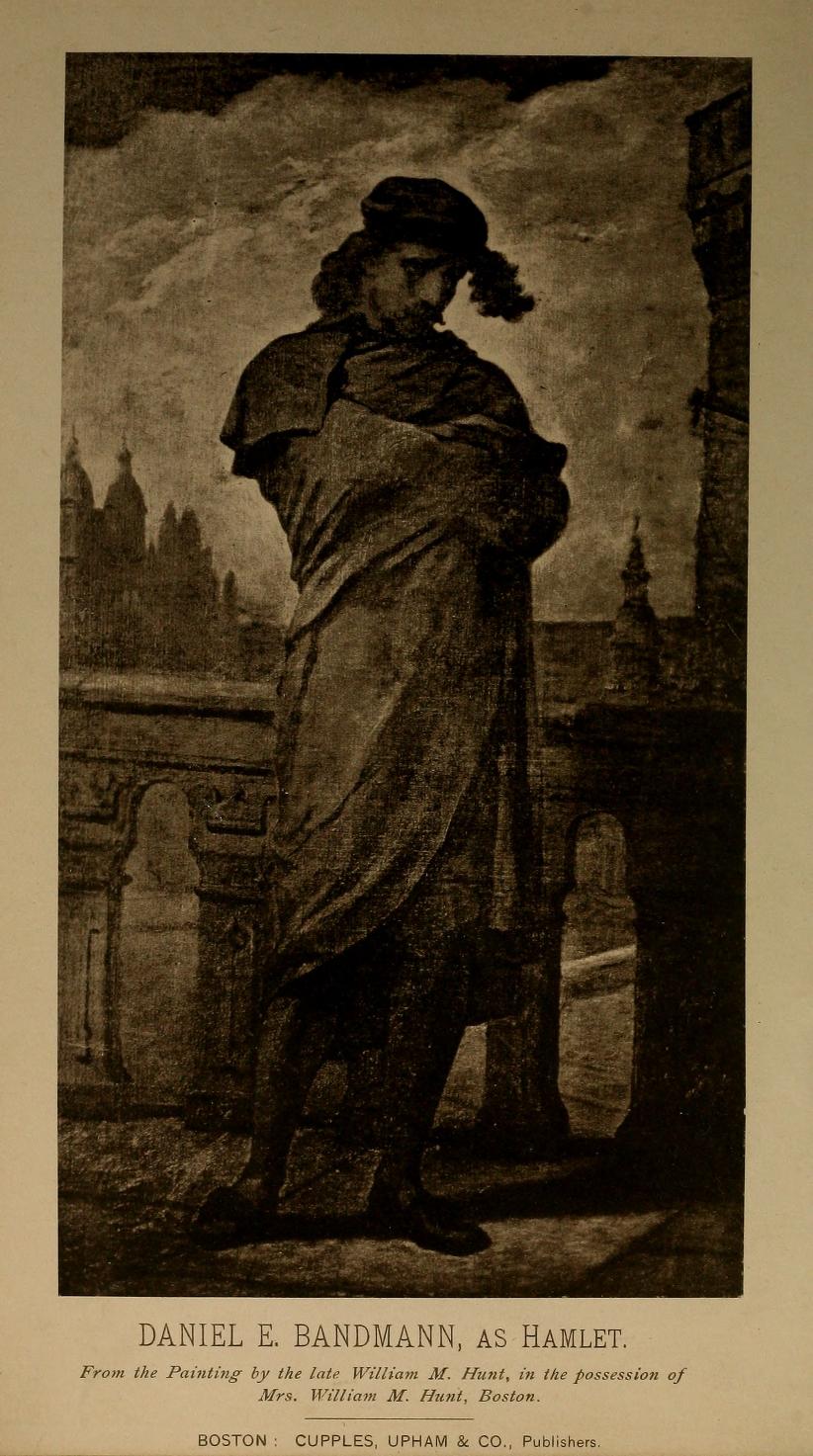

Other travellers provide insights in the Australian colonies from surprising angles, such as the singer David Kennedy in Kennedy's Colonial Travel (1876) and Daniel Bandmann in An Actor's Tour: Or Seventy Thousand Miles with Shakespeare (1885). James Holman became a celebrity as “the blind traveller” and volume 4 of his A Voyage around the World, Including Travels in Africa, Asia, Australasia, America (1834) focusses on his extensive travels through Australia.

Business travellers wrote about their vast geographical journeys, including the entrepreneurial George Francis Train, who wrote An American Merchant in Europe, Asia, and Australia (1857), a global travel narrative driven by commercial interests. Others such as Sir Richard Tangye made multiple trips to Australia to extend his empire-wide tool manufacturing and engineering business. Tangye described how he filled the long voyages by writing travel accounts, which included Reminiscences of Travel in Australia, America and Egypt (1883) with delightful sketches by E. C. Mountfort and Notes of My Fourth Voyage to the Australian Colonies (1886).

-

Others travelled for health reasons, from England or from other colonies such as India, including Ninety Days' Privilege Leave to Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand (1885), published pseudonymously by 'J.D.' Comprehensive searching has enabled us to identify most of the pseudonymously published books, although some (like J.D.) remain elusive and we welcome further identifying information. Travel between India and Australia was encouraged by those such as Henry Cornish in Under the Southern Cross (1879). Nor should it be assumed that travellers were all privileged white Britons, as Fazulbhoy Visram shows in A Khoja's Tour in Australia (1885):

travelling from Bombay in 1885, the Khoja businessman Fazulbhoy Visram promoted travel for his fellow Muslims, gently chiding the ‘large number of native gentlemen to whom travelling and its advantages are scarcely known, and some are even unaware of the existence of such a glorious country as Australia!’. Visram’s enthusiasm for trans-colonial trade and his comparison of colonial political systems (he is acerbic about democratic privileges available in Australia compared to India) reminds us that travel by white Britons was only one part of the story. (Johnston, 'Australian Travel Writing,' 275).

You might be interested in...