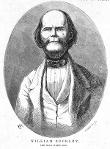

William Buckley was born to a humble family in 1780 at Marton, Cheshire. At age sixteen, William became apprenticed to a bricklayer, but soon after enlisted in the army. He was later said to be an exemplary soldier, large in height, possessing great and strength and highly disciplined. In 1799, he was sent to Holland to join the fight against Napoleon's forces. After being wounded in combat, Buckley was given leave and returned to England. Little concern was shown for the welfare of returned soldiers at the time, and Buckley apparently turned to crime. In 1802 he was convicted on a charge of possession of stolen property, and sentenced to fourteen years penal transportation. In 1803, he boarded the Calcutta, bound for Australia.

The Calcutta, along with a supply ship Ocean, sailed with some 150 crew and over 300 male convicts, and had a special mission: under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins, they were to sail to Port Phillip and establish a new settlement there. Reverend Robert Knopwood was also aboard the Calcutta and kept a journal of this expedition. In October, the ships reached Port Phillip and the convicts began work on the new settlement. The work was difficult and escape attempts were frequent; skirmishes between the colonists and local Indigenous people also took place. In late 1803, the decision was made to abandon the area and move to Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania). On December 27, after hearing the news, a group of convicts including Buckley fled into the night.

One convict was shot upon fleeing and another returned to the settlement almost three weeks later. This man, M’Allender, asserted that the remaining members of the escaped party were either dead or lost in the bush, and the search for them was subsequently called off. In the ensuring months, the colonists prepared the ships for travel to Tasmania. The settlement was deserted, the half-finished buildings stripped of all their materials and the fields left to the weeds, by mid 1804.

William Buckley had not perished in the bush through; while his fellow prisoners had decided to turn back (with only M’Allender managing to make it back alive) Buckley was determined to obtain liberty. After days of wandering aimlessly with little food or water, he stumbled on a small hut with food stores. He met with a group of Aboriginal men at the hut who left him unharmed but he again fled into the bush in fear for his life. After a few months of living of the land, Buckley came across a Indigenous burial mound, marked by a spear. This spear would prove to be his salvation.

Buckley slept under a tree that night, the spear beside him. In the morning he was greeted by two Wathaurung women who recognized the spear as belonging to the great warrior Murrangurk. The two women brought their husbands who proclaimed Buckley as the returned spirit of the warrior. He was introduced to the tribe and became a highly esteemed and renowned figure in the Aboriginal community. For thirty-two years, Buckley lived among this Aboriginal tribe where he married and became a valuable counselor. During this time he became totally integrated into the Aboriginal way of life, even forgetting much of his English skills.

In 1835, Buckley heard word that a group of white men had been seen along the coast. Buckley approached the camp, which had been established in order to find a suitable area for settlement, in full Indigenous attire and was received with astonishment by the colonists. The tattoos on his arm identified him as a convict and after a few days he was able to regain enough English to explain his situation and provide his identity. Buckley also had a hand in quelling the discontent that his Aboriginal friends had towards the colonists. Word of Buckley eventually made it to Tasmania and he was provided with a pardon.

Buckley was appointed as an interpreter for the settlers as they explored the surrounding areas in 1836. Notably, he accompanied Joseph Tice Gellibrand and William Roberston on a westward expedition to present-day Geelong where the party encountered a group of Aboriginals that Buckley had once lived with. By 1837, Buckley decided to travel to Tasmania where he worked a number of odd jobs. He obtained a job as assistant store-keeper at the Hobart Immigrant's Home where he met his future wife. Julia Eager was a Irish settler with a young daughter whose husband had been killed by Aboriginal people on route in Sydney. The pair were married in 1840.

The Buckleys spent the next sixteen years in Hobart Town. The family survived on a pension from the Convict Department along with funds raised by close friends. He dictated his thirty-two years spent in the Australian wilderness to writer John Morgan in 1852 who composed the autobiographical novel, The Life and Adventures of William Buckley. Many details of these texts are clearly embellished yet it remains the only source of information for Buckley's time living with the indigenous population. In 1856, William Buckley was sailing in a small boat at Greens Pond, near Hobart, when he slipped overboard and drowned. He was seventy-six years old and survived by his wife.

1086170760543178857.jpg

1086170760543178857.jpg