The following are a series of short, self-contained research pieces that have come about as a result of the World War I project.

Click on the tiles below to read each piece.

Some of this content originally appeared on the AustLit blog. It is an evolving series and more research insights will be added here as the year progresses.

Gunner Frank Westbrook was one of the many soldier poets of World War I. Before the war he had worked as a cook. He was 25 years of age when he enlisted in September 1914. The following month he left Melbourne with the 2nd Field Artillery on HMAT Shropshire, bound for Egypt. During the war Westbrook saw action at Gallipoli and later on the Western Front. Despite being wounded, he survived the war and eventually returned to Australia.

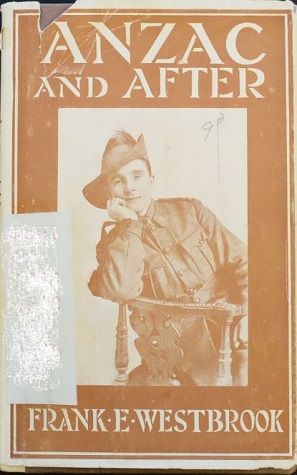

Westbrook's literary output appears to have been almost entirely limited to the war years. He evidently claimed that he had not written a single verse prior to enlisting, and from what we can establish, he wrote only a handful of works after war’s end. On one level Westbrook’s poems are unremarkable, though the fact that many were penned at Gallipoli is of itself perhaps remarkable. It is unclear whether Westbrook ever became particularly well known among the reading public. Several of his poems were published in the Australian newspapers during the course of the war. His modest wartime selection, Anzac and After (1916), which was kindly reviewed in the press, became available in Australia in late 1916. Some years afterwards he published a second selection of poems, Echoes of Anzac (1930), which included many of the works from Anzac and After.

Regardless of Westbrook’s standing as a poet, he is an interesting figure in that during the months prior to the Gallipoli campaign, he became involved in what amounted to a public slanging match with official Australian war correspondent Charles Bean. At the time, Australian troops had been stationed in Egypt. Initially it had been intended that they would undergo further training there and then be deployed in Europe on the Western Front. However, this was to change when Churchill’s plan to attack the Gallipoli peninsula was put in train.

As things transpired, by late December 1914, the behaviour of Australian troops on leave in Cairo was becoming something of a problem for military authorities, who were concerned at the level of public drunkenness and the incidence of venereal disease within the ranks. Under instructions from Major General Sir William Bridges, commander of the 1st Australian Division, war correspondent Bean briefly raised the matter in a dispatch, which was published in the Australian newspapers in January and February 1915.

Over the following weeks, Bean’s dispatch came in for a good deal of attention in the press, with Bean often being criticised for having insulted the reputation of the Australian troops in Egypt. When the troops in Egypt became aware of the dispatch, they too entered the fray, with many writing letters to family and friends in Australia, protesting their innocence and expressing their annoyance with Bean. A number of these letters were in turn published in the press.

It was in this context that Westbrook penned his scathing satirical poem, ‘To Our Critic’, which lambasted Bean for having defamed the Australian troops in Egypt and ridiculed him as a whining wowser. Initially published in the Egyptian Mail, the poem circulated widely in the Australian newspapers during April 1915.

The outcry at Bean’s dispatch appears to have reached such a level that Bean found it necessary to issue a clarification, stating (with a good deal of justification) that he had in effect been misrepresented, whilst at the same time praising the Australian troops. However, far from calming the waters, Bean’s clarification served only to further irritate poet Westbrook, who penned a second barb in reply, ‘On Our Critic’s Apologies’.

From an historical perspective the episode is interesting because it reveals how at this point, the authorities in Australia were still learning how to control and manage the way in which the war was reported in the press. But the episode is also notable because it is one of the few instances where we find the literature of the war being at odds with officialdom. No doubt the authorities, Bean included, learned a good deal from what had transpired and from this point on, controversies involving the supposed indiscipline Australian troops weren't allowed to play out in the newspapers in this manner. As it happened, with the landing at Gallipoli, the episode was quickly overtaken by events and it faded into the background.

Dorothy Frances McCrae was one of the many, many patriotic poets whose stirring verses appeared in the Australian newspapers and magazines in the early months of World War I.

In many respects, McCrae's poems are typical of a good deal of the war literature of the pre-Gallipoli period, in that they reflect a way of writing about the war, a way of imagining the war, which was as yet untempered by the reality of war. Like so much of the creative outpouring of the early months of the war, McCrae's poems express a level of exuberance and enthusiasm that became less common as the war progressed, when the casualty lists began appearing in the newspapers and the reality of the war began to hit home.

McCrae's first selection of wartime poems, Soldier, My Soldier!, was published in mid October 1914, at which point Australia's only engagement in the war had involved the seizure of German New Guinea by a small expeditionary force. Her second selection, The Clear Call, was published in late July 1915, when the Gallipoli campaign had yet to run its full course and when people at home in Australia still had little knowledge of events there.

Without exception, McCrae's wartime poems are wildly patriotic. Fuelled by outrage at the German invasion of Belgium, she views the war as a noble and just cause, as a glorious and heroic adventure, where Australians might prove their worth and affirm their loyalty to Britain and Empire. Men are implored to fulfill their duty and enlist in the armed forces, whilst women are encouraged to support their menfolk and be steadfast in their resolve.

Regardless of what you make of McCrae's poems, she is an intriguing figure. In many of her poems she assumes the voice of the wife or the mother, in effect claiming the authority of a woman whose husband or son has enlisted–which was of course at odds with the facts. McCrae's husband was a Church of England clergyman who spent the war years in Australia and New Zealand, and at the time her children were of primary-school age.

A few examples:

'Second Thoughts' (1st stanza)

I wished you back at my breast

When I saw this war descend,

Now I'd scour the east and west

For another son to send;

'The Empire's Call' (3rd stanza)

The Empire is calling, my son, my son.

I who gave birth to you, echo her call,

Fight till the Death, till the battle is won,

Deem it an honour if fighting you fall -

'The Gift' (1st stanza)

All that I have, England, I give to you.

Gladly through tears, I see my son depart.

You gave me all, so I, with grateful heart,

Give you my child, so loyal and so true,

But perhaps McCrae's most remarkable poem is where she writes of her real life brother, Geoffrey Gordon McCrae, who had then just enlisted and was later killed at Fromelles.

'Geoffrey' (2nd stanza)

On the day that you volunteered

We were smitten down by grief,

But skies have changed and winds have veered,

And now - of our joys, it's chief,

For 'tis the greatest, grandest thing

To give a soldier to the King.

All up, McCrae's early wartime poems are a world away from works such as Randolph Bedford's 'The Earl of Anzac' (1916) or Mary Gilmore's 'The Mother' (1917), which were written later in the war, when the human cost of the conflict was being keenly felt at home.

Dorothy Frances McRae's second book of patriotic poetry, published in 1915

Dorothy Frances McCrae's first collection of patriotic poetry, published in 1914.

Gunner Frank Westbrook's collection of poetry, much of it written at Gallipoli.

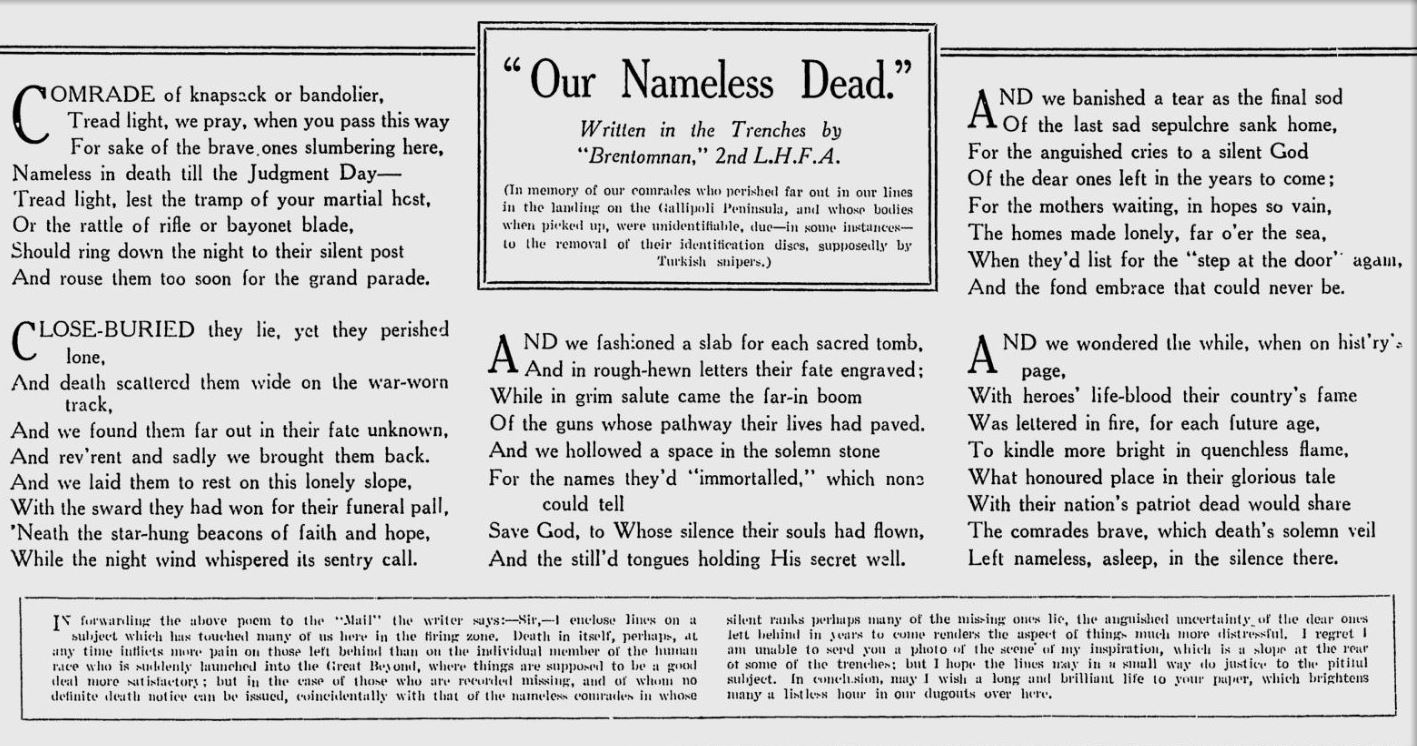

Soldier writer Tom Brennan's tribute to comrades killed at Gallipoli.

Dorothy Frances McRae's second book of patriotic poetry, published in 1915

Dorothy Frances McCrae's first collection of patriotic poetry, published in 1914.

Gunner Frank Westbrook's collection of poetry, much of it written at Gallipoli.

Soldier writer Tom Brennan's tribute to comrades killed at Gallipoli.

Without doubt, one of the saddest aspects of the AustLit World War I project has been where we've discovered soldier writers who were either killed during the war, or who died from the effects of the war in the months and years after war's end.

Tom Brennan ('Brentomnan') was one of seven children born to John and Mary Brennan, of Kilkenny, Ireland. In the years before World War I he migrated to Australia, along with his younger brother Joseph. At the outbreak of war in 1914, both Tom and Joseph were living in Brisbane. They enlisted at about the same time in December 1914, and then in February 1915 they both left Brisbane together on HMAT Seang Choon, bound for Egypt. Tom served as a stretcher bearer with the Light Horse, whilst Joseph served as a private with the 9th Battalion AIF. Both brothers served at Gallipoli. Joseph was seriously wounded and died in a military hospital at Alexandria in early July 1915. Tom survived Gallipoli and then spent the rest of the war in Egypt and Palestine. In August 1916, he was mentioned in despatches for his actions at Romini, and he was subsequently awarded the Military Medal for gallantry at Bir-Al-Abd. However, by war's end Tom developed a severe psychiatric illness. He was initially evacuated to England, where he spent a lengthy period in English military hospitals, before being returned to Australia as a convalescent in late 1919. He died of ‘exhaustion’ in Brisbane in September 1920.

During the war, as 'Brentomnan' (an anagram of 'Tom Brennan'), Tom became well known in Australia for his poem 'Our Nameless Dead', which he penned in late 1915 as a tribute to comrades killed at Gallipoli. The poem was published widely in the Australian newspapers at the time. But he was perhaps even better known for his poems and other pieces which were published in the soldiers' magazines the Cacolet (which he briefly edited) and the Kia-Ora Coo-ee. Indeed, he was arguably one of the more talented of either magazine's contributors. However, perhaps due to the circumstances of his death, and that he appears not to have had any immediate family in Australia, his poetry was quickly forgotten. Three of his poems appeared in post-war anthologies, but beyond this, none of his works have again appeared in print.

Of course, one of the most intriguing elements to this sad, sad story is whether Tom's family back home in Ireland ever learned of his wartime literary accomplishments. Notably, Tom's younger brother Anthony also served in World War I, though with the Royal Irish Rifles. As luck would have it, Anthony survived the war and lived to write an account of his wartime experiences, which is now held at the Imperial War Museum in London.

You might be interested in...